A review of the architecture exhibition “The Other Architect –Another Way of Building Architecture,"curated by Giovanna Borasi, written for The Journal of Architectural Education.

The subject is there only by the grace of the author’s language. – Joyce Carol Oates1

Right now, otherness is a political category with a highly charged social valence. To be other is to be alien, not included, held apart. Disturbingly different or inferior. A threat, a surplus. Though recent uprisings on both sides of the political spectrum have drawn attention to the power dynamics of exclusionary practices, the concept of otherness precedes our current political climate. For many of us on the outside, to be ostracized as other already was, and has always been, commonplace. To exist on the margins is, for some, simply a part of everyday life.

Thus, to call an architecture exhibition “The Other Architect” brings up all sorts of questions about what constitutes the norm versus the alternative, or the center versus the periphery. Curator Giovanna Borasi’s choice of adjective implies that the broad swath of projects included in this exhibit, which span the 1960s to the present, are adversarial, novel, and counter-cultural. Like the brigade of shows over the past few years that have fed our fascination with the “radical”, “hippie modern” sixties and its legacy of alternative practices, “The Other Architect” adopts this curatorial turn, to showcase “architects who expanded their role in society to shape the contemporary cultural agenda without the intervention of built form.”2 Its varied selection of twenty-three unusual case studies includes a road trip taken by Liselotte and O.M. Ungers to catalogue utopian communes; a televised architecture charrette called Design-A-Thon; Giancarlo De Carlo’s International Laboratory of Architecture and Urban Design; a yacht cruise conference organized by Constantine Doxiadis and Jacqueline Tyrwhitt; a mobile library dubbed AD/AA/Polyark; and Pidgeon Audio Visual, a mail order lecture kit; among others. These are placed alongside more recent projects such as the conferences and publications of Anyone Corporation; the Center for Urban Pedagogy’s exhibitions and educational programs; AMO’s branding reports; and Eyal Weizman’s university course and consultancy, Forensic Architecture.

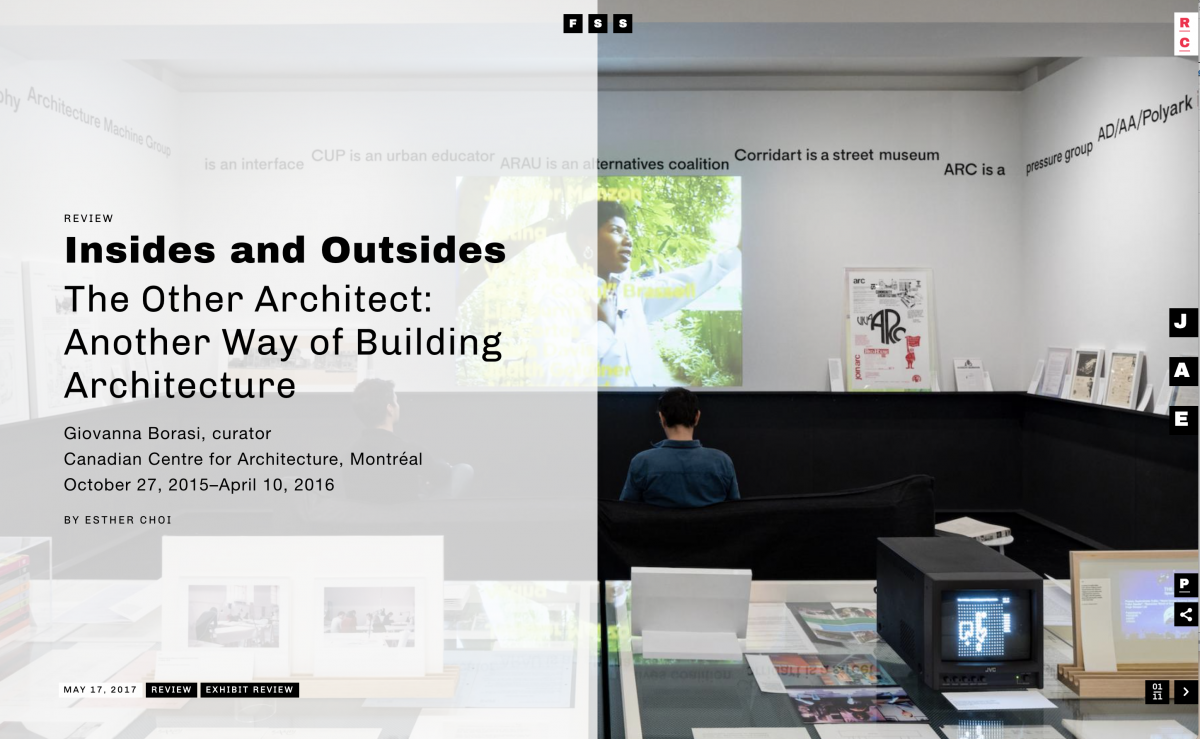

Despite the eclectic range of architectural projects, the show is mainly a display of documents, calling to mind Benjamin Buchloh’s characterization of the sixties’ Conceptual art practices as an “aesthetics of administration.”3 Borasi has marshaled an impressive array of archival material spanning four decades. Taking the form of reports, memos, letters, photographs, and some time-based documentation culled from events and conferences, the institutional authority of this “information” takes the place of museum didactics and curatorial interpretation. While the exhibition’s first installation at the Canadian Centre for Architecture (October 27, 2015-April 10, 2016), designed by MOS Architects, made use of the exhibition walls as a graphic extension of the written page to spatialize each case study, its second installment (also designed by MOS) in the close quarters of the Arthur Ross Architecture Gallery at Columbia GSAPP (September 16- December 2, 2016) exacerbates a sense of info-matic bureaucracy through its arrangement of low stools and long tables containing printed ephemera. The gallery takes on an air of managerial office work: viewers are expected to sit down and read.

Yet for all of its attention to archival research, at the heart of “The Other Architect” is the presentation of a set of symptoms without the provision of a diagnostic. Ultimately, it’s unclear what the criteria is for the exhibition’s hodgepodge selection of projects, beyond their basic testament to the novel things that architects have thought and done outside of traditional building design. Case studies are not organized historically or thematically, nor analyzed in terms of their embeddedness in wider economic and social processes. Numerous points of contradiction also arise amongst the projects, making it difficult to understand if a project’s otherness is qualified by an active critical stance it has taken against the forces of inequality in the world, or its antagonism to insular disciplinary debates. Instead, the exhibition’s narrative implies that these projects innately contributed to the discipline in an almost mechanical way, by funneling information into an imaginary reservoir or cloud of architectural “data.” We are repeatedly told that architectural knowledge constitutes a particular type of epistemological inquiry and a form of practice in its own right, but the implications of these presuppositions are unclear.

One point of contention that arises throughout the projects is the subtext of a pernicious dualism between architecture and everything else. Despite the role that documents have played in other research-based exhibitions as an index of political and economic forces,4 “The Other Architect” seems to wield its documents for radically different purposes: paperwork symbolizes an opportunity to untether the architect from the limiting constraints of professional practice and the world at large. Indeed, the show seems to position reality—that is, the state of things as they actually exist—as a kind of burden. In the opening lines of Borasi’s introduction to the catalogue, she writes: “for as long as architecture has been reduced to a service to society or an ‘industry’ whose ultimate goal is only to build, there have been others who imagine it instead as a field of intellectual research: energetic, critical, and radical.”5 For Borasi, the architect’s retreat from building seems to hold experience as such in suspension, allowing the architect to think about and do other things.

Yet amongst the dossiers that document these alternative forms of practice, we see vectors of “the real” creeping in. Most troubling are the instances when architects demonstrate a flagrant lack of critical engagement with the vectors of power that make the task of architectural knowledge production possible. Take for instance, Cedric Price and Frank Newby’s Lightweight Enclosures Unit, a commission from the British government to survey the predominantly military-sponsored development of pneumatic structures in 1969. Similarly, it’s farcical to imagine that radical alterity could be used to describe AMO’s participation in the luxury global apparel market when consorting with clients like Prada and Conde Nast. (Within the context of this exhibition, the nobility of these architects remains intact, even when their interests dovetail with capitalist and military exploits.) And while some architects enthusiastically acquiesce to the power of market forces, other case studies demonstrate the architect’s flagrant disregard of one’s privilege and biases. The exhibition’s presentation of the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies (IAUS), for example, does little to problematize the IAUS’s treatment of race and class in its research project on Harlem as demographic markers of a “symbolic real”, rather than actual conditions outside its doorsteps.6

The unevenness of the projects included in the show, and the lack of analysis throughout, is a detriment to the practices that actively seek to reflexively interrogate the discipline or use architecture as a tool for cultural critique and intervention. Whereas Eyal Weizman’s Forensic Architecture has wielded architectural analysis to excavate geopolitical tensions, Price and Newby’s project, in contrast, focused inadvertently on the literal inflation of them. Or consider the urban activist “counter-projects” of the Brussels-based Atelier de Researche et d’Action Urbains, which openly critiqued profit-driven development and the demolition of working class neighborhoods caused by infrastructural expansion in the late 1960s and ’70s. Likewise, the Center for Urban Pedagogy’s lateral organization, which integrates community-building workshops in secondary schools for transformative ends, stands in direct opposition to the IAUS’s approach, which leveraged its Ivy-League connections for government-funded research subsidization.

What the passel of paperwork on display seems to suggest is that there has been, at least since the mid-twentieth century, a persistent need for the architect to formalize and validate her or his intellectual activity as “knowledge” through the protocols of white-collar bureaucracy, rather than the blue-collar labor of trade work. And in this light, the exhibition’s title is misleading: “The Other Architect” is not a show about otherness per se, but rather, a look at an historical moment in which architecture decided to separate itself from the building industry to participate within a post-Fordist information economy. This is perhaps why the report format becomes so central to the exhibition’s display, as it seems to constantly reiterate the scenario of an analogue database desperately in need of management. Borasi equates the practice of architecture with knowledge production, stating that: “when the architect produces and codifies this research it becomes a useful tool for others, and once again the architect’s role shifts into something other than that of the traditional figure. Now the architect is someone who makes architecture possible even when they do not construct anything.”7 But this equivalency between discovery, codification, and “fact” raises even more questions: Is this information circulated in the democratizing manner that Borasi implies to “trickle down” to the communities it takes as its subjects? Could we not consider the desire to codify knowledge as an outgrowth of the modernist obsession with systematization; in sum, a device for homogenizing and standardizing ideas, rather than giving birth to wild, new ones? Might research not lend itself to organically adopt novel forms in response to the particular contexts and conditions under which it is generated?

The concept of otherness in this exhibition is more than a problem of language: it’s a sign of how hegemonic narratives of architecture are subtly perpetuated, romanticized, and canonized. A claim for alterity cannot be made without problematizing what it means to be a stranger in both a profession and a society, without examining if the internal politics of particular social formations of practice reflect an actual alternative, or if they are merely circumstantial consequences. A simple look at the range of subjectivities in the exhibition, for instance, shows how racial minorities and the working class were often the subjects, rather than authors, of study. To imagine that architecture, made of paperwork or bricks, could exist independently of core conceptualizations of class, race, gender, or political economy is a vacuous exercise. Rather than facing this type of investigation as an unimaginative moral burden, we might query, instead, what privileged few can afford the luxury of forgetting about these social realities in the first place.

The strategy of “The Other Architect” seems endemic to the status of “information” in our post-Internet era: Although the rampant accessibility of data has, on the one hand, promoted a democratic leveling of voices and sources, it has also produced a sense of confusion between expertise and opinion, erasing important categorical distinctions, values, and motives. But if curation is but one of the many skills that the architect can leverage to engender new and transformative cultural perspectives, the exhibition can act as an opportune platform for prototyping innovative, theoretical approaches that treat history and its documents as a site for productive contestation.

Who fits in the category of the other architect? Who gets to count? There are a number of exits this question could take. To investigate the concept of otherness in architecture would go beyond the simple skills of arithmetic or data collection. To address this question of otherness, we’d have to direct critical attention to the contexts in which knowledge is authoritatively produced. The task would demand that we become astute observers of how insides and outsides are constructed.8 Indeed, to recuperate the discipline’s many, othered architects would require letting go of the stories and images that we’ve clung to, in order to excavate, reanimate, and ultimately re-write history through its margins.

- Joyce Carol Oates, “Against Nature” (1988)

- “The Other Architect,” Press release, Columbia GSAPP. Web. https://www.arch.columbia.edu/exhibitions/37-the-other-architect

- Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, “Conceptual Art 1962-1969: From the Aesthetics of Administration to the Critique of Institutions” in October 55 (1990): 105-43.

- See, for instance, Sylvia Lavin’s discussion of the status of the document in Rem Koolhaas’s curation of the 14th Venice Architecture Biennale. Sylvia Lavin, “Too Much Information,” in Artforum 53 (1) (September 2014): 347-53, 398.

- Giovanna Borasi, “The Other Architect: Another Way of Building Architecture,” in The Other Architect (Montreal: Canadian Center for Architecture, 2015), 362.

- See Lucia Allais, “The Real and the Theoretical, 1968” in Perspecta 42 (2010): 27-41.

- Borasi, “The Other Architect,” 365.

- Here I refer to a point about leftist resistance made by writer Sara Marcus: “I think that people who come into a leftist state of mind, often that comes in part from having a strong ability to identify with whoever is being left out of something, and that can very easily spill into assuming that you, too, are being left out of something. That feeling isn’t necessarily coming from the outside; it’s coming from one’s own keen observations and analyses of the ways insides and outsides get constructed.” An interview with Sara Marcus. http://www.nassauweekly.com/an-interview-with-sara-marcus/. Web. Accessed March 16, 2017.