In Young and Giroux's "Infrastructure Canada", the camera’s cool, seemingly impartial gaze is pointed at similar infrastructural typologies shown in their day-to-day use. Quotidian and habitually ignored, they are, however, instrumental to the economic, industrial, and ideological operations of the country. Rather pointedly, the installation presents filmic portraits of these apparatuses crucial to the post-industrial operations of the nation-state, in contrast to how the country’s ambiguous personhood and incommensurate power have been embodied historically through the figuration of land and foliage in landscape painting.

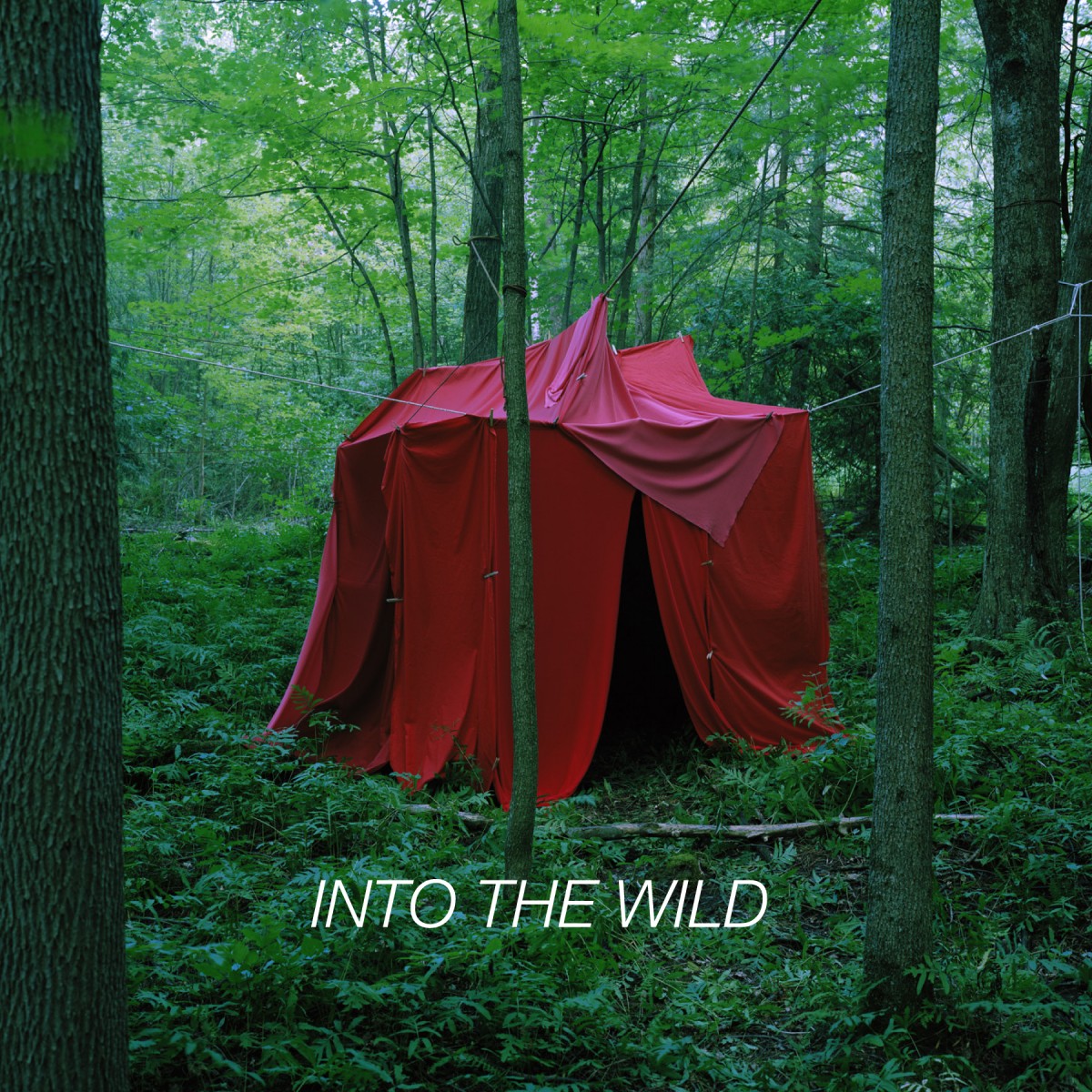

Into the Wild. Hamilton Artists Inc.

September 5 – October 17, 2015

Curated by Caitlin Sutherland

Artists include Sonny Assu, Jason Brown, Leisure (Susannah Wesley and Meredith Carruthers), Duane Linklater, Alex McLeod, Darren Rigo, Elinor Whidden, Daniel Young & Christian Giroux, as well as select works from the Art Gallery of Hamilton’s permanent collection.

Overcast skies loom above hydro poles, train tracks, an overpass, and a shipping dock in "Infrastructure Canada". These massive objects, conduits for the organization and transport of people, energy, and resources, are framed as protagonists in an endless cycle of vignettes. Quiet, steadfast, slow, we feel their weighty presence, and their anonymity, against the backdrop of rural, modernized, and post-industrial landscapes.

Like the Anonymous Sculptures of Bernd and Hilla Becher, whose conceptual photographs of the German manufacturing economy featured systematic views of gas tanks, water towers, coal mines, grain elevators and other oft-ignored structures, Young and Giroux’s time-based studies frame a similar set of objects and borrow from the visual conventions of Neue Sachlichkeit, the New Objectivity. In "Infrastructure Canada", the camera’s cool, seemingly impartial gaze is pointed at similar infrastructural typologies shown in their day-to-day use. Quotidian and habitually ignored, they are, however, instrumental to the economic, industrial, and ideological operations of the country. Rather pointedly, the installation presents filmic portraits of these apparatuses crucial to the post-industrial operations of the nation-state, in contrast to how the country’s ambiguous personhood and incommensurate power have been embodied historically through the figuration of land and foliage in landscape painting.

It is thus fitting that Young and Giroux’s systematic pictures do not declare a singular identity. Rather, Infrastructure Canada presents a series of idiosyncratic landscapes bound by a structured formal approach. Their intention, unlike the Bechers, was not to emphasize the homogeneity of these infrastructural elements and landscapes, but rather to highlight their subtle differences through clinical compositional methods. Unspectacular details distinguish places and territories, identifiable only to viewers habituated to these nuances. The discreet markers of terrain—such as the slight changes in fauna or the distinctive quality of light in a particular region—create a topological and topographical mosaic of a country similarly lacking, to borrow from Gramsci, a unified “common sense.”

Whereas for the Bechers these mass-produced typologies communicated the rationale of the Modernist functionalist doctrine, which heralded the machinic logic of technological systems as a symbol for German national identity, Infrastructure Canada asks us to consider the relationship between the power of infrastructure and land politics in a wholly different context. How does a country which has defined itself historically by its resource prosperity, in many ways aligning with American regional planning initiatives in the 1930s, come to terms with its problematic history of acquiring and marketing these resources? What parallels can be drawn between the notion of the resource rich nation-state and the insidious partition that conceals the social conditions and processes that contribute to this idea or image on an ongoing basis? And furthermore, how might these photographs of Canada’s infrastructural spaces contribute to an understanding of “landscape” and “nature”— terms and concepts that are protean and malleable—as cultural constructs in themselves?

Unlike the landscape photography of the “New Topographics” which often focuses on the residues of human alterations to the environment, Young and Giroux’s durational portraits frame infrastructure not as a spatial substratum of geopolitical, social and economic processes, but as technological mediums in their own right. Theirs is not a cautionary tale of environmental mismanagement, but rather, an object-oriented study of systems, protocols, and economies. Bridges, gas pumps, dams, and electricity lines are not static things but catalysts that initiate, manage, and execute various procedures by pumping, scooping, pouring, trafficking, connecting, and dispersing. They are instruments whose material and technological histories are intricately imbricated in the vectors of labour, legislation, globalization, and bureaucracy.

In this way, Infrastructure Canada asks us to not only better understand the specific material and technical configurations of the spatial products of infrastructure, but to also question how their aesthetic qualities lend themselves to hold particular forms of power in the world. As generic, unmemorable, and easily reproducible things, they possess a peculiar capacity to circulate in global networks fluidly, rapidly, and forcefully. In this way, Infrastructure Canada offers an object lesson in infrastructure to those of us concerned with the built and managed environment, challenging us to examine how we might leverage and re-circuit the logic of these spatial systems into conditions of possibility rather than ascendancy.

Into the Wild explores expectations of Canadian wilderness— the fictitious narratives and mythology surrounding a hyper-aestheticized Canadian landscape—how it is romanticized, and its role in the construction and perpetuation of a unifying national identity. The eight artists in this exhibition present nuanced entry points contrasting idealized representations of Canadian wilderness and northerness with charged works highlighting the affects of colonial, infrastructural and environmental interventions as well as Canadians’ continued efforts to domesticate and insert themselves into these constructed mythologies. Works by Sonny Assu and Alex McLeod clearly illustrate the constructed nature of landscape while introducing audiences to the exhibition’s post-wilderness framework. Jason Brown, Duane Linklater and Young & Giroux emphasize the capacity of these idealized representations to act as social hieroglyphs through the social relations they conceal. Leisure, Darren Rigo and Elinor Whidden probe continued attempts to insert ourselves into these pristine spaces, primarily through leisure activities. These insertions, present in each of the works on display, are key markers when considering how this exhibition situates itself and contributes to contemporary post-wilderness debate. This exhibition explicates, for the general public and critically invested art audiences alike, the political and contested nature of landscape in this nation. Landscape is political. It is framed. And most importantly, it is never neutral.