An essay, commissioned by SSENSE, that explores Michèle Lamy's attempt to tap into the dark, minimal, “tribal” and "prehistoric" narrative of Rick Owens’s brand, reimagined through the projection of an aspirational lifestyle.

I have to admit that I never completely understood Rick Owens’s meteoric rise to fame. Part of this may be due to generational circumstance. Owens first emerged as a designer in his own right in 1997. At the time, I dressed not too dissimilarly from the eponymous “sporty Goth” garb that has since characterized his street wear label, DRKSHDW. Though I was decidedly less a jock than a Goth, I was a walking nineties cliché: gaunt, misunderstood, and sulking to emo and black metal records in the suburbs.

But the mid-to-late nineties was not only a time of pouting and posturing: it was also a moment of anti-corporate politicking and fanzine writing, a time of sarcasm and cultural theory. For those of us who voluntarily dressed like Romulans—with jet-black hair and raised eyebrows— our ill-fitting dark uniforms and hand-sewn punk patches were an act of communication; they signaled a growing sense of anti-corporate dissatisfaction. Indeed, the worst that one could do was “sell out.” It was perhaps one of the last moments when clothing, like music, formed subcultures based on common values.

Rick Owens came onto the fashion scene precisely when a kind of cultural shape shifting was about to take place, as the regalia of hardcore punk and metal slowly became diffused into mainstream culture and absorbed by mass-market consumption. A master appropriator, Owens was able to successfully import the do-it-yourself and improvised ethos of this countercultural expression into a trillion dollar global apparel market. Since then, Owens has developed his own tribe—609,000+ followers on Instagram, to be precise—voguing to the beat of Byrell The Great or Dat Oven in drop crotch cashmere pants. Indeed, his trademark can now be found in all aspects of his brand. There are his clothes: draped, dark volumes of contrasting proportions and sculptural silhouettes. There are his shows: press-worthy spectacles of blazing catwalks, sorority hip-hop dancers, foam waterfalls, and male models letting it all hang out. And then there’s Owens himself: performative, controversial, and always up for shock, most recently immortalized in Christeene’s “Butt Muscle” video with his waist-long black locks shoved into the performer’s anus.

So when news circulated that Owens opened his ninth flagship store in SoHo late last year, it came with a great sense of anticipation. Though his former store on Hudson Street was fairly raw and unadorned, many expected a level of theatricality in his new haunt, given that it would be representative of a guy who had a composite photograph taken of him pissing into his own mouth. Certainly his other stores had elements one could call “quirky” at best: his Paris headquarters, for instance, features a naked wax statue of Owens urinating on the floor. Owens, too, seemed to understand architecture’s importance. In an interview for 032c, he referred to clothing as the first step towards architecture.1

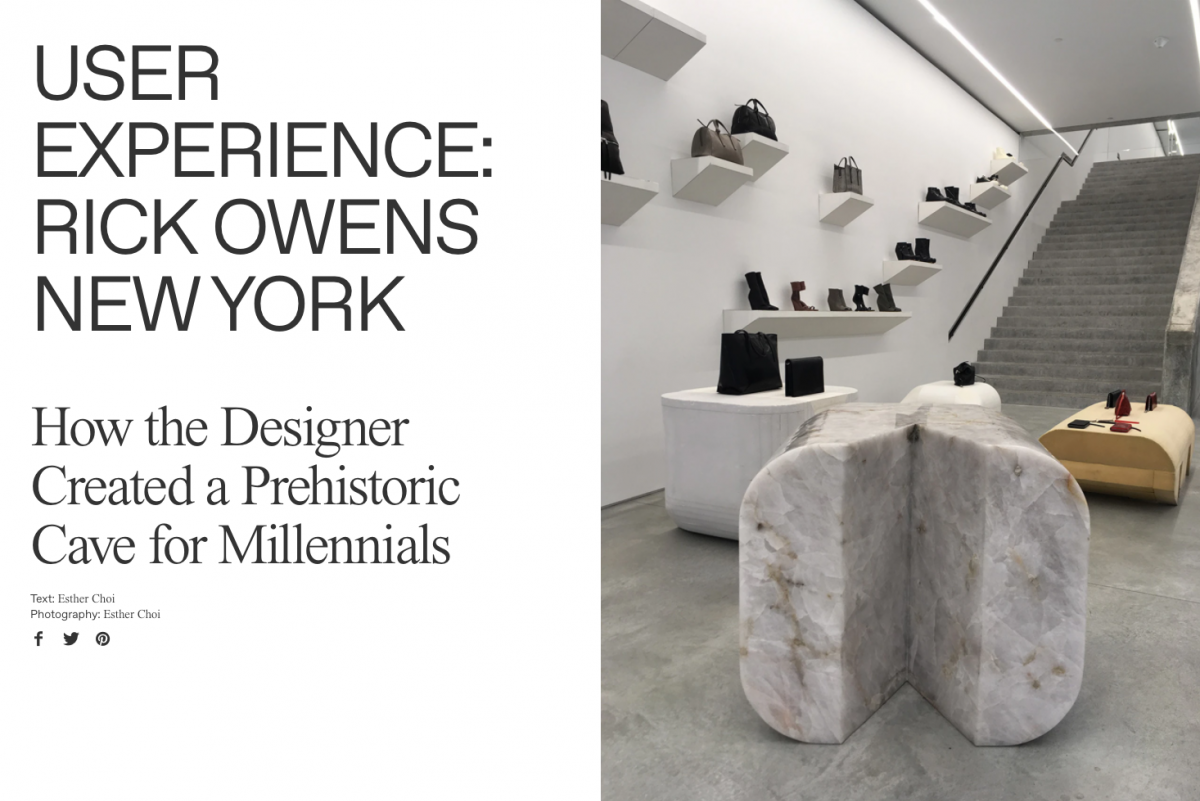

But when I arrived at Owen’s outpost, the building’s lackluster green façade – left from its former haunt as a ladder store – and Owen’s modest signature on the windows seemed to signal I was in for something rather tame and unassuming: considerably less Mordor, and more loft living. A cheerful twenty-something employee greeted me. We proceeded to make small talk as an eclectic mix of middle aged men and young street wear enthusiasts adorned in carnivalesque costumes perused the goods on display. “Who exactly is the main clientele?” I asked, confused. “A lot of creatives in their forties and fifties,” he mused, “and, of course, a lot of performers like rappers and musicians.” Indeed, this polarizing clientele—at once low-key and spectacular—seemed to sum up the store’s design impulses. Designed by Michèle Lamy, Owens’s furniture designer, wife, and “fairy witch”, the store features a fairly normative shell of white walls and a concrete floor. With the exception of a monumental concrete staircase that bisects the store in two, most of the geometry appears to have been left intact.

Still, through smaller moves, it becomes clear Lamy has attempted to tap into the dark, minimal “tribal” narrative of Owens’s brand, reimagined through the projection of an aspirational lifestyle that clients can hope to attain. Evoking a prehistoric feel, furniture primarily designed by Lamy is scattered throughout the space, adopting associations to rocks, landforms, and animals. Concrete slabs have an aged patina. In a Brutalist manner, materials speak to the customer through their own physical presence rather than the use of dramatic lighting or “special effects.”

Owens and Lamy’s sculptural furniture are the true focus of this space, populating the first floor as follies that lead the shopper through a promenade of handbags, signature shoes, and housewares. Doubling as display plinths and seating, these faceted boulders are constructed from and covered with unusual materials: camel hide, concrete, marble, plywood, alabaster, and polystyrene. Although Owens has been designing furniture since 2007, for his home and retail spaces, only recently did it become an extension of his brand available for purchase. Likewise, the store was ultimately envisioned as an experimental space to test prototypes for the exhibition of Owens and Lamy’s furniture, now on view at The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Foam seating sculpted into Owens’s signature “prong” shape used in his previous furniture designs are available in single and double sizes, with camel skin versions running in the €30 000 range. Likewise, the theme of Paleolithic domestication is pronounced in the store’s housewares, such as made-to-order dark terracotta and copper plates and cutlery made of sterling and bone designed by Owens and Lamy. Their cave is replete with a totemic stone fireplace housed in the rear of the store, echoing a large sculptural column made of glass, steel and crystal near the entrance.

Like Owens’s clothes, there is a contradictory impulse in Lamy’s design objects in their irreverence to details. Suspended between a simultaneous awareness of and an indifference to craftsmanship, they are at once charming and unbearably awkward. Her furniture feels more like artifacts from a prehistoric age; their charm is their imperfection. Lamy has taken pains to leave their crusty, rough seams intact, and this motif of imperfect seaming runs subtly throughout all scales of the space. The language of seams is carried into pronounced gaps that reappear periodically throughout the store, from the floor, wall boards, and staircase, to the ceiling and mirrors, and even the dressing rooms’ door jambs. The store’s geometry feels carved into, from strips of recessed fluorescent lighting that run the length of the space, to the staircase’s inset handrail. On the second floor, a more traditional retail space containing racks of Owen’s ready-to-wear collections, faceted mirrors reflect the lighting tracks into laser-like patterns. The effect is that the weight, textures, and physicality of building materials are emphasized and registered as the body weaves through displays.

Just as fashion can assimilate a uniform and empty it of its meaning, materials and contexts are approached with a similar sense of flippancy and moxie. In Lamy’s objects, highbrow and lowbrow comingle fluidly. Foam boulders flank a 1.5-ton slab of polished crystal from Pakistan featured prominently on the first floor (the largest in the United States). Foam convincingly adopts the look stone at times, while precious stone might as well be foam. Likewise, though these objects look and seem archaeological—a motif that runs throughout Owens’s curated Instagram feed which often features pottery and decorative objects culled from museum collections—they are made by artisans in the present moment. As artifacts they carry the residues of their contemporary construction, yet seem to want to operate outside of their own time. In this troglodyte’s paradise, the difference between the synthetic and organic, past and present, is one and the same.

I found myself sitting in a marble chair on the second floor, contemplating the image of the “urban primitive” lifestyle that Lamy has so carefully crafted—a cave of objects that is at once unattainable, thus appealing to fashion’s love of fantasy, and totally ornery. It was at this moment that I caught a glimpse of my reflection in the mirror, wearing a designer jumpsuit designed expertly to look like the anonymous uniform of a factory worker—a reminder of how fashion can communicate cultural pathologies and critique in the most subversive ways. In these post-Internet times, the contemporary narrative of the hunter-gatherer—that advocate of slow food, craft, and bespoke production—has adopted varied and unassuming forms, from millennial coffee bean roasting, to Owens and Lamy’s high-end primitivism. Certainly Owens and Lamy’s SoHo store seems to drive this theme home, by tapping into our most primal, late capitalist desire to retrieve a sense of authenticity. Its primitive narrative seems to intuit a sense of lost freedom: from its insistence on the eternal present (for what does it mean to be prehistoric than to be literally devoid of history?) and perpetual novelty, to the dream of being a subject that is at the dawn of a new moment of self-creation, outside the bounds of social norms, rules, and expectations. If Owens’s fashion shows are ceremonial gatherings for his tribe, Lamy’s retail sanctum seems to complete the story, offering a habitat for his army of Cro-magnon urbanites.